The claim: Fat (obese) people make up most of the world's COVID-19 deaths.

On 4 March 2021, the World Obesity Federation released a new report titled COVID-19 and Obesity: The 2021 Atlas. The WOF used World Obesity Day to publicize their report, with the highlight that nearly 90% of COVID-19 deaths have been in countries with high rates of obesity. Over the next few days, several mainstream news organizations reported on the story, including The Washington Post, whose headline mimicked the main talking points from the tweets sent from the WOF marking #WorldObesityDay.

Obesity is a disease that does not receive prioritisation commensurate with its prevalence and impact, which is now fastest rising in emerging economies.

— World Obesity (@WorldObesity) March 4, 2021

We've just released our new report 'COVID-19 and Obesity: The 2021 Atlas' for #WorldObesityDay ⭕

➡️ https://t.co/sRaCjG5hA9 pic.twitter.com/Q326y6Orfk

Most virus deaths occurred in countries where majority of adults are overweight, report finds https://t.co/PwUTbsAo3t

— The Washington Post (@washingtonpost) March 5, 2021

A new study found that obesity and the Covid death rate is closely linked https://t.co/92OueWz4bj pic.twitter.com/RX4NiOn6QC

— Forbes (@Forbes) March 5, 2021

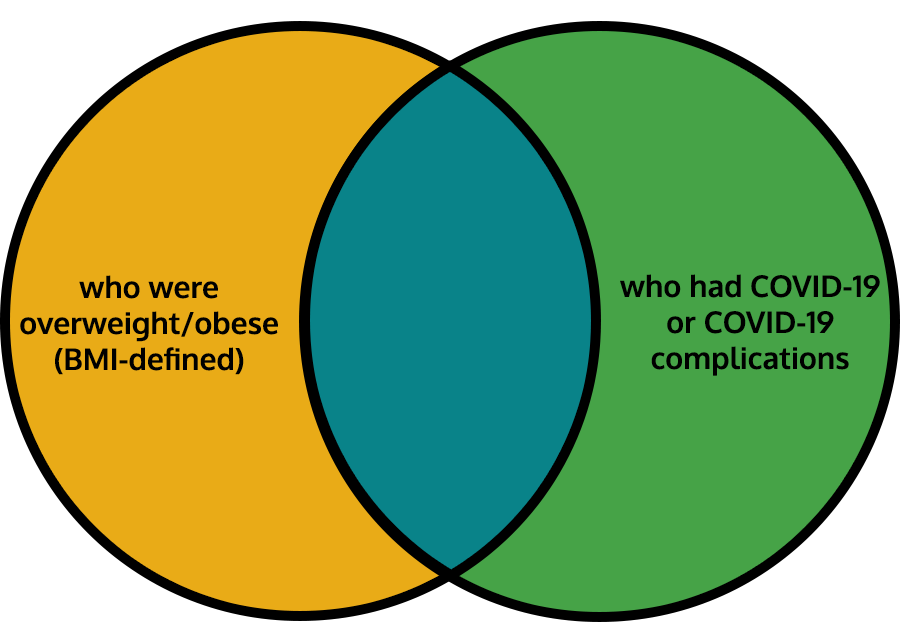

What most people took away from this report and the subsequent articles, and then shared and discussed on Twitter, was that most of the people who have died from COVID-19 have been fat or obese, and that being fat is a leading cause of death by COVID-19.

High obesity rate in U.S. to blame for having one of world's worst COVID-19 rates, study findshttps://t.co/3hIxGnizIb

— Patricia Dickson (@Patrici15767099) March 4, 2021

David, studies have now shown that most of the virus deaths came from people who were overweight https://t.co/P1BsApmJLe

— Jack Posobiec (@JackPosobiec) March 5, 2021

Hundreds of thousands of lives and trillion of dollars could have been saved if we had addressed the root causes of obesity before the COVID-19 pandemic hit according to a World Obesity Federation report: https://t.co/gHPLNwHky9 #WorldObesityDay

— Orla Woodward (@OrlaWoodward) March 4, 2021

But what does the WOF report state? How is "majority overweight" defined? Are most of COVID-19 deaths due to people being fat, overweight, or obese? And what exactly do any of those terms mean?

The verdict: do fat people make up the most numbers of COVID-19 deaths?

Mary Ellen Cagnassola at Newsweek did some digging into the claim, and summarizes key points of the WOF's report, noting that the WOF analyzed data from secondary sources, including Johns Hopkins University and the World Health Organization Global Health Observatory. Cagnassola finds that the analysis identifies a "linear correlation between a nation's COVID mortality and obesity rate", and that it does not specify the percentage of overweight or obese individuals of the overall COVID-19 mortality rate.

The WOF report does not state that nearly 90% of COVID-19 deaths were fat individuals, nor does it state that being fat causes COVID-19.

The report does state that "2.2 million of the global 2.5 million COVID-19 deaths reported in February occurred in countries where more than half the population is classified as overweight" (Cagnassola, emphasis added).

What information is actually in the report?

The WOF's report was released on World Obesity Day, observed on March 4, 2021. The report had several key points, including:

- an estimated 2.2 million, out of an estimated 2.5 million, of COVID-19-related deaths worldwide occurred in countries with an overweight population above 50% (6),

- COVID-19 mortality rates were ten times higher in countries with overweight populations above 50% than in countries with overweight populations under 50% (20),

- overweight individuals were hospitalized at higher rates than non-overweight individuals (12), and

- the estimated cost of COVID-19 over the period 2020 through 2025 could be between $6 and $7 trillion (24).

The WOF defines overweight according to a body mass index (BMI) of 25 kg/m2 and above, and obese as 30 kg/m2 and above (6). The report also contains the facts and numbers for each of the 160 countries included for study (34-222).

Cagnassola emphasizes that the report does not provide a global percentage of people who were overweight and who also died of COVID-19.

Did people misunderstand the report's messaging?

Patricia Dickson posted an article on Twitter claiming that the United States has a high COVID-19 mortality rate due to its large obese population. However, the article never states that obesity is a direct cause of COVID-19 death rates; it does state that the WOF's report claims "the connection may account" for death rates in the U.S. (Curl). The headline is inaccurate, likely leading readers to believe that fat causes death via COVID-19.

Further, in response to a tweet about the pandemic's longevity due to anti-masking efforts, Jack Posobiec argues instead that most COVID-19 deaths were "people who were overweight". Again, as Cagnassola debunked in the Newsweek fact check, this is not accurate! The misunderstanding is most likely due to misreading one of the WOF's key points from their report, that 2.2 million deaths, or about 88% of all COVID-19-related deaths worldwide occurred in countries where at least 50% of the population could be classified as "overweight" (World Obesity Federation 6). Cagnassola clarified that the deaths "occurred in countries" with a majority overweight population, which does not necessarily mean that those individual deaths were overweight people themselves.

Orla Woodward's tweet argues that if the "root causes of obesity" were addressed well before the pandemic began, hundreds of thousands of deaths could have been avoided, in addition to saving trillions of dollars, and states that information comes from the WOF's report. Yet, the report admits that the costs of COVID-19 due to overweight "cannot be easily assessed," and contends that most of the economic losses are a result of overburdened healthcare systems and government lockdowns (24). The WOF's $6 to $7 trillion estimate of overall costs in the five-year period from 2020 through 2025 is an educated guess based on a secondary source that approximately 29.5% of COVID-19 hospitalizations were overweight individuals. Woodward is partly correct, though, in that the report does assert that hundreds of thousands of deaths might not have occurred if all countries surveyed had overweight populations under 50%.

Additionally, both Dickson and Woodward use the term obesity in their tweets, which echoes the vocabulary of many on Twitter discussing the report, and the connection (if any) between weight and COVID-19. Although the report was published by an organization with the word obesity in its name, the report's baseline category is overweight, using a BMI of 25 kg/m2; obese, on the other hand, is 30 kg/m2. This terminology may have confused readers, especially since the report was released and publicized heavily on World Obesity Day.

These tweets seem to demonstrate a misunderstanding of the report on the side of the reader, and the statements posted can therefore be labelled as misinformation.

- Misinformation

- a statement, story, article, or other piece of information that a person shares, publishes, or posts, unintentionally misunderstanding that the information is false, inaccurate, or misleading (Jack; Wilkinson)

These misunderstandings lead people to "misinform themselves" (Kahan 4, emphasis original), thus allowing them to in turn misinform others.

What was the goal in posting misinformation about the report?

The WOF originally released the report to highlight the correlation between countries with majority overweight populations and high COVID-19-related mortality rates in order to "avert future crises" (3).

Based on the phrasing of the tweets quoted above, and of various other tweets discussing this topic, one hypothesis of the users' intentions in posting the misinformation is placing blame. The word blame is specifically used in Dickson's post, to name high rates of obesity as a main cause of widespread outbreaks in the U.S. When French suggests that anti-masking efforts have greatly extended the pandemic, Posobiec instead shifts responsibility onto people who are overweight, not those who refused to wear masks. Lastly, Woodward holds obesity accountability for the monumental numbers of COVID-19 death.

Why did people believe the resulting misinformation?

Repeated information

The more you hear a piece of information, even if it is false, the more likely you are to believe it (Altay 2; Clark). This is supported by research published by Frederick, et al. who reveal that antifat stigma increases the more a person is exposed to fat-negative information, leading to beliefs that fat poses health risks, that weight is within a person's control, that fat people should be charged more for healthcare and health insurance, among others (543). In addition to the prevalence of antifat articles a person reads, Saguy and Almeling find

the news media do dramatize more than the studies on which they are reporting and are more likely than the original science to highlight individual blame for weight (53).

Existing biases

Everyone knows that being fat is bad, right? This "conventional wisdom" (Harrison) is accepted by everyday people as hard science, when that's not always the case. This antifat stigma, drilled into us by a barrage of news stories and weight loss advertising, results in negative opinions of fat people, inferior healthcare for fat people, misinformation spread about fat people, and sometimes targeted harassment of fat people. "People's perception of what the facts are is shaped by their values" (Kahan 2, emphasis original) and therefore are more likely accept as fact information that already agrees with their predispositions (Kahan 4; Kahne and Bowyer 5).

Trending topics

As Clark puts it in rule number five, "rumors reflect the zeitgeist". COVID-19 has been a global pandemic for over a year (at the time of this writing), and is still very much at the forefront of everyone's mind. With vaccines now rolling out across the U.S., many are anxiously waiting on their eligibility as certain groups have been prioritized in early phases, including "obese" individuals.

Why did people then further spread the misinformation?

Emotional fodder

Between the misinformation surrounding the WOF's report, and the early phases of the vaccine rollouts, stress, uncertainty, and anger are only a few of the emotions bubbling to the surface for some people, bringing up a lot of fear and speculation. For example:

- obesity caused COVID-19, which in turn triggered financial instability for small-business owners (@FreeThink68);

- children are burdened with wearing masks because fat people exacerbated the pandemic (@woody20005);

- fat people being in a priority group for the vaccine is "special treatment" that will lead to other undesirable groups, such as serial killers, moving ahead in the queue (@tbarksdl);

- people no longer care for their neighbors, and have ignored their "civic duty" by refusing to lose weight (@GeezLiberty); and

- obesity is the reason that the pandemic even happened at all (@AlexPKeetn).

MSM today - obesity is the main driver of Covid deaths. So we've all been locked away for a year because some people can't stop stuffing their faces.

— John Karter (@JohnKarter01) March 4, 2021

Covid kills fat people...

— Harley Mal (@MichelleMal716) March 9, 2021

And we really shut down the economy, schools, and life for this? Because fat fucks can’t catch their breath? Jeeeeez https://t.co/JZGjfUpe7F

I’m really f’n angry today. So angry that Morrison thinks he has the right to infect me & my family and my whole damn community with Covid while he has his fat arse protected by Pfizer. I’m so angry my heart is pounding. Red hot F*CKING anger.

— Jacaranda (@Randall87454048) March 9, 2021

Although Garrett's article examines Facebook, the same theories apply: emotions, especially anger, drive people to continue the spread of misinformation. When that misinformation seems to confirm a person's existing biases, it riles up that anger, prompting a swift share of that post.

Simplicity

Rubin suggests that social media platforms such as Twitter provide an effortless user experience for people to post and repost information, and those platforms are complacent in their approach to misinformation and hate speech (1025-1026). In addition, social influences can gain large followings, contributing financial benefits to those platforms, further disincentivizing their motivation to regulate misinformation spread.

Conclusion

Marwick notes three parts of a sociotechnical model of social media spread:

- people derive meaning from the interactions on social media;

- media is often designed with an intended purpose for its audience; and

- the delivery method of the media can affect the inferred meaning.

Here, users on Twitter read the posts from the WOF regarding its new report, and took away their own (mis)understandings. While the WOF has its own purpose in posting about its report — publicizing its release — users had either similar or different agendas in reposting it, depending on their interpretation of the report or the subsequent misinformation. As Twitter is a social media platform that fosters communication and sharing, retweeting that misinformation became as easy as clicking a button.